In September 1947, the US Air Force had a problem. A series of reports about mysterious objects in the skies leaves the public tense and the military perplexed. The Air Force needs to quickly find out what is going on and launches an investigation called “Project Sign.”

In early 1948, the team realizes that they need some outside expertise to examine the reports they are receiving, specifically an astronomer who can determine which cases are easily explained by astronomical phenomena such as planets, stars, or meteors.

For J. Allen Hynek, then 37 years old and director of Ohio State University’s McMillin Observatory, it would be a classic case of being in the right place at the right time or, as he occasionally lamented, the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Beginning of the Adventure

Hynek had worked for the government during the war developing new defense technologies, so he already had a high level of security clearance and was the natural choice.

“One day I received a visit from several men from the technical center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, which was only 60 miles from Dayton. With some obvious embarrassment, the men eventually brought up the subject of ‘flying saucers’ and asked if I would like to serve as a consultant to the Air Force on the subject. The work didn’t seem like it would take much time, so I agreed,” Hynek later wrote.

Hynek didn’t know that he was about to begin a lifelong journey that would make him one of the most famous and, at times, controversial scientists of the 20th century. Nor could he have guessed how much his own ideas about UFOs would change over that period, as he persisted in bringing rigorous scientific investigation to the subject.

“I had barely heard of UFOs in 1948 and, like every other scientist I knew, assumed they were nonsense,” Hynek recalled.

Project Sign lasted a year, during which the team analyzed 237 cases.

In Hynek’s final report, he noted that about 32% of incidents could be attributed to astronomical phenomena, while another 35% had other explanations, such as balloons, rockets, or birds. Of the remaining 33%, 13% did not offer enough evidence to provide an explanation. The remaining 20% provided investigators with some evidence, but it could not yet be explained.

The Air Force was loathe to use the term “unidentified flying object,” so the mysterious 20% were simply classified as “unidentified”.

In February 1949, Project Sign was succeeded by Project Grudge.

Although Project Sign offered at least a pretense of scientific objectivity, Grudge seemed to have despised science from the beginning, as did its name, which suggests “anger”.

Hynek was not involved in Project Grudge and said the premise of the project was that UFOs simply could not exist.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the report, published in late 1949, concluded that the phenomena posed no danger to the United States and were the result of mass hysteria, deliberate fraud, mental illness, or conventional objects that witnesses misinterpreted as supernatural and concluded that the subject did not deserve further study.

But UFO incidents continued, including some intriguing reports from Air Force radar operators, and the national media began to treat the phenomenon more seriously.

LIFE magazine ran a cover story in 1952 and even respected TV journalist Edward R. Murrow devoted a program to the topic, including an interview with Kenneth Arnold, the pilot who in 1947 spotted mysterious objects over Mount Rainier in the state of Washington, and popularized the term “Flying Saucer” – to find out more details about this case read here: https://conexaoufo.com/en/kenneth-arnold-the-pilot-who-sighted-a-ufo-in-1947/

The Blue Book Project

The Air Force had little choice but to revive its investigations into what came to be called Project Blue Book.

Hynek joined Project Blue Book in 1952 and would remain with it until its end in 1969.

As before, Hynek’s role was to review reports of UFO sightings and determine whether there was a logical astronomical explanation. Normally, this involved a lot of paperwork, but every now and then, an intriguing case would come up and he would get a chance to field work.

He discovered something he might never have learned simply by reading the files: how normal the people who reported seeing UFOs tended to be.

“The witnesses I interviewed could have been lying, they could have been crazy, or they could have collectively hallucinated, but I don’t think so. Their standing in the community, their lack of motive to perpetrate a hoax, their own bewilderment at the turn of events they believed they had witnessed and often the great reluctance to talk about the experience, all of this demonstrates a subjective reality to your experience with UFOs”, says the astronomer in his book The Hynek UFO Report.

For the rest of his life, Hynek would live with the ridicule that people often had to endure when reporting a UFO sighting. Which caused countless numbers of other people to never speak out. Not only was it unfair to the individuals involved, it meant a loss of data that could have been useful to researchers.

“Given the controversial nature of the subject, it is understandable that scientists and witnesses are reluctant, because their lives will change. There are cases where their home is broken into. People throw stones at their children. There are family crises, divorce and so on. You become the person who saw something that other people didn’t see. And there’s a lot of suspicion attached to that,” says Jacques Vallee, co-author with Dr. Hynek of the book The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects.

Keeping an Eye on the Skies and the Soviets

In the late 1950s, the Air Force faced a more pressing problem than UFOs. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union surprised the world by launching Sputnik, the first artificial space satellite and a serious blow to Americans’ sense of technological superiority.

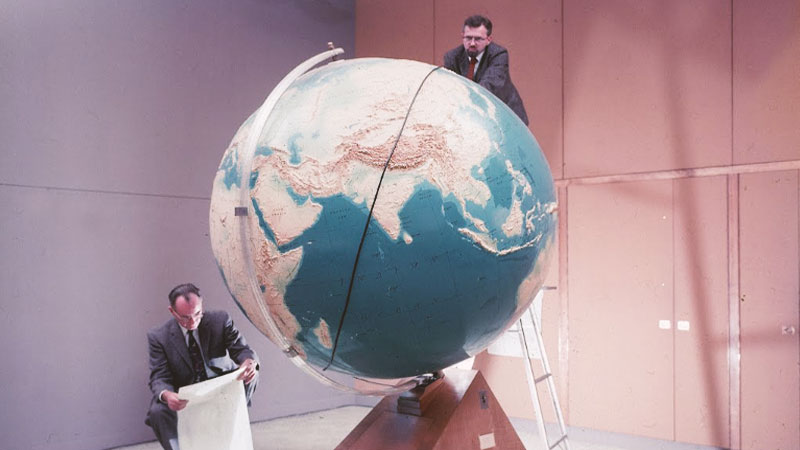

By this time, Hynek had moved from Ohio State to work on a satellite tracking system at Harvard and suddenly, Hynek was on TV, giving frequent press conferences to assure Americans that their scientists were closely monitoring the situation.

On October 21, 1957, he appeared on the cover of LIFE Magazine with his boss, Harvard astronomer Fred Whipple and his colleague Don Lautman.

With Sputnik circling the Earth every 98 minutes, often visible to the naked eye, many Americans began looking skyward and UFO sightings continued to increase.

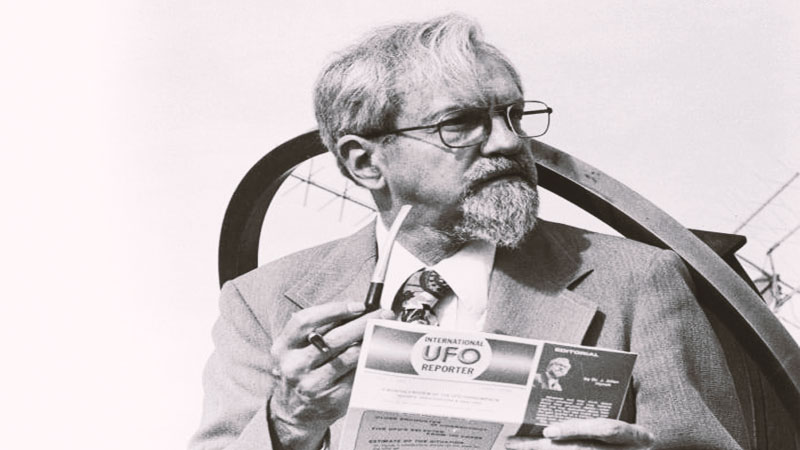

By the 1960s, Hynek had emerged as the nation’s and perhaps the world’s leading UFO expert, cited widely for his role as a scientific advisor to Project Blue Book, but behind the scenes, he chafed at what he considered to be the main point of the project: debunk UFO sightings.

He also criticized the project’s procedures, claiming that the Blue Book team was inadequate, its communication with outside scientists was frightening, and that its statistical methods were a sham, but Hynek remained on the project anyway.

“The most important thing was that Blue Book had the data storage, poor as it was, and my association with the project gave me access to that data,” Hynek wrote.

Hynek often angered UFO debunkers, but did not always please believers.

In 1966, for example, he went to Michigan to investigate several reports of strange lights in the sky. When he offered the theory that it might have been an optical illusion involving swamp gas, he found himself widely ridiculed by the press and “swamp gas” became a joke for newspaper cartoonists and two Michigan congressmen, including Gerald R. Ford, who would later become U.S. President, were offended by the apparent insult to their state’s citizens and called for a Congressional hearing.

Testifying at the hearing, Hynek saw an opportunity to make the case he had been making to the Air Force for years, but with little success.

“Specifically, it is my opinion that the body of data, accumulated since 1948, deserves a thorough examination by a civilian group of physical and social scientists for the express purpose of determining whether a major problem truly exists,” Hyenk said during the hearing .

The Air Force then established a civilian committee of scientists to investigate UFOs, chaired by Dr. Edward U. Condon, a physicist at the University of Colorado.

Hynek did not participate in the committee and lost his faith in it two years later, when the Condon Report was released, which he considered disproportionate, poorly organized and biased.

Although the report cited several UFO incidents that its researchers could not explain, the conclusion was that: “further study of UFOs probably could not be justified”.

It was exactly what Hynek didn’t want and in the following year, 1969, Project Blue Book was definitively closed.

A New Chapter

Meanwhile, sightings continued around the world and Hynek joked: “UFOs apparently didn’t read the Condon Report”.

In 1972, his first book, The UFO Experience, was published, where Hynek introduced classifications of UFO incidents called “Close Encounters”.

- Close Encounters of the First Kind: UFOs seen close enough to notice some details;

- Close Encounters of the Second Kind: The UFO had a physical effect, such as burning trees, scaring animals, or causing car engines to suddenly stop;

- Close Encounters of the Third Kind: Witnesses report seeing occupants in or near a UFO.

Although less remembered now, Hynek also provided three classifications for more distant contacts. Those involved UFOs seen at night (nocturnal lights), during the day (daylight discs) or on radar screens (radar/visual).

One of his Hynek classifications, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, would become the title of a Steven Spielberg film released in 1977.

Hynek received $1,000 for use of the title, another $1,000 for rights to use stories from his book, and another $1,500 for three days of technical consulting.

He also had a brief cameo in the film, playing an impressed scientist when he sees the alien ship appearing up close atop Devil’s Tower.

In 1978, Hynek retired from teaching, but continued to collect and evaluate UFO reports for the Center for UFO Studies, which he founded in 1973 and continues to operate today.

Hynek died in 1986 at age 75, the result of a brain tumor.

He did not solve the UFO riddle, but perhaps more than anyone else, he made trying to solve it a legitimate scientific pursuit.

“The main thing I learned from my father was the importance of keeping an open mind. We still don’t know everything there is to know about the Universe, there may be many aspects of physics that we still don’t know about,” said his son Joel Hynek.