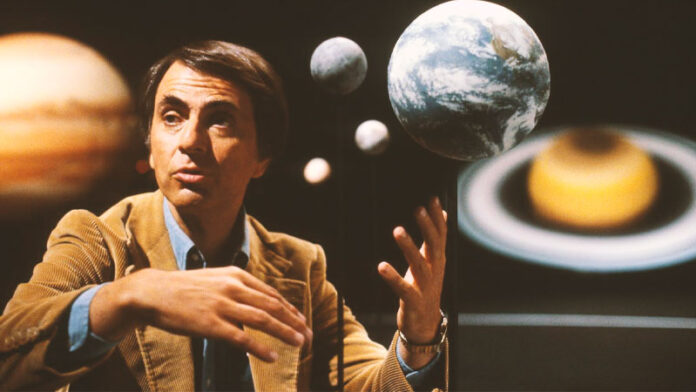

The Cosmos series, made by Carl Sagan and his wife Ann Druyan in the 1980s, is one of the most formidable examples of the breadth and effectiveness that scientific dissemination can achieve through audiovisual means.

Aboard the Ship of Imagination, freed from the shackles of space and time, he could travel wherever he wanted, like the dandelion petals blown at the beginning of the first episode of the series.

This ship was the perfect vehicle to transport more than 400 million human beings, from more than 60 nations, on a cosmic adventure.

The Story of Sagan

Carl Sagan grew up reading science and science fiction books, and as an adult, he used to mention an episode that left a deep impression on him: when his parents took him to the 1939 New York World’s Fair, at the age of 5, he marveled at the futuristic pavilions.

“It showed that there was a world beyond the working-class neighborhood of Brooklyn. Several exhibits at the fair had optimistic visions of the future, including space travel. He retained that optimism and grew up to develop probes,” says William Poundstone, author of Carl Sagan: A Life in the Cosmos.

Among the things he saw that day, perhaps the most awe-inspiring was the burial of a time capsule. It was the basis for one of his most emblematic projects: the Golden Record, launched in 1977 aboard the two Voyager probes, which is nothing more than a time capsule engraved on a gold-plated copper vinyl, which has already left the Solar and will wander for the next billion years. It’s like a message in a bottle to potential alien intelligences.

“He was in many ways comparable to a poet, who used the hard facts of the world to convey the deepest emotions. Sagan’s relationship to astronomy was, in many ways, a spiritual relationship,” says Poundstone.

Sagan coordinated the team that selected 115 images and 90 minutes of music that would best represent our species, as well as greetings in 55 languages.

“Hello from the children of planet Earth”, says the recording on the Golden Record, which was in charge of Nick Sagan, son of Carl Sagan and artist Linda Salzman, who says that the best example of his “surreal childhood” was seeing releases from rockets instead of playing on the playground.

It was during Nick’s childhood that Carl, by then already well-established as director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University, began to acquire public figure status. The Golden Record’s popular appeal and the credibility of winning a Pulitzer in the same year caught media attention.

The career focus, however, strained her marriage to Salzman, which was soon to end. In the development of the Golden Record, Sagan fell in love with the creative director of the project, his third and final wife, with whom he remained until the end of his life: Ann Druyan, producer and writer who not only accepted her husband’s works, but also collaborated with them.

“He was lucky with a woman who was able to accept that he was this incurable workaholic,” notes biographer William Poundstone.

Sagan realized early on that he was unable to confine his interests to academic labels. Since childhood, he was also fascinated by the origin of life, which made him approach biology. It was in this context that he met his first wife, biologist Lynn Margulis, with whom he had two children. Throughout his career, he published scientific articles detailing models of what life could be like on other worlds and, with these studies, he helped to found the multidisciplinary field of astrobiology.

Another great contribution of Sagan was in the area of planetary science: he did a thesis and obtained a doctorate degree on the workings of the atmosphere of Venus.

“He taught his students that planets are places, truly other worlds. It encouraged us to think about what it would be like to be on these other worlds,” says astrophysicist David Morrison, who was among these students and is now a Senior Scientist at NASA.

Carl Sagan was also a consultant and contributor to NASA, and he was involved in a controversy that says a lot about how he saw the democratization of science. Almost no scientist at the agency believed that the probes should have cameras.

“Sagan insisted that the public was paying for the missions, and that he would relate to the photos, not words or numbers. He finally convinced the doubters. So every time you look at a high resolution image of the planets, that’s a legacy of Sagan,” says William Poundstone.

But there are mainly two people who are direct heirs to that legacy, both responsible for the updated sequel to Cosmos, which aired in 2014: Ann Druyan herself, now president of the Carl Sagan Foundation and executive producer of the new series, and the charismatic astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who was responsible for presenting the new version.

Tyson always says that on December 20, 1975, exactly 21 years before Sagan’s death, when he was just another 17-year-old from the Bronx trying to choose where to study, he was greeted by Sagan himself at Cornell. The astronomer showed him the university and then took him to the bus station. As it snowed heavily, Sagan gave him the phone number of his own house and asked him to call in case of unforeseen circumstances to spend the night with his family.

“I have a duty to answer students who are asking questions about the universe in the same way that Carl Sagan answered me,” said Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Timeline

Carl Sagan was married three times and had five children. Throughout his brilliant career, he created fields of study, was influential at NASA and inspired millions of people around the world. See remarkable moments in the astronomer’s life.

1934 – Sagan is born in Brooklyn, New York. He studies in public schools and from an early age loves science books. At the age of 5, he visits the New York World’s Fair, a futuristic event that impresses him greatly.

1951 – Wins a full scholarship to study physics at the University of Chicago. There he meets biologist Lynn Margulis, with whom he has two children: writer Dorion Sagan and programmer Jeremy Sagan.

1960 – Obtains a doctorate degree in astronomy with a thesis on the atmosphere of Venus. In the following years, he established himself as a consultant and advisor for NASA, directly influencing the space program.

1963 – Separates from Margulis and starts teaching astronomy at Harvard. He soon becomes a popular figure among the students, but his interests in exotic issues arouse the suspicion of his colleagues.

1968 – Moves to Cornell University, where he would stay for the rest of his life. There he develops new disciplines: planetary science and astrobiology. He marries Linda Salzman and, two years later, Nick is born.

1977 – The Voyager probes are launched. Sagan leads the team on the Golden Record, a time capsule with records of the human species, and meets Ann Druyan, the project’s creative director, and his future wife. The book The Dragons of Eden, which discusses the evolution of human intelligence, wins the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction. Recurring appearances on TV shows and magazine covers begin.

1980 – Cosmos airs on PBS to critical and public acclaim. He marries Ann Druyan, writer and producer of the series, with whom he has two children, Sasha and Samuel.

1985 – Contact is published, his only novel, about a radio message from an alien civilization that is received by humanity. Sagan is also dedicated to the fight against the use of nuclear weapons.

1996 – Dies on December 20, at age 62, in Seattle, with complications from pneumonia. Two years earlier, he had been diagnosed with myelodysplasia, a disease that prevents the development of bone marrow cells.